Why the Permanence of Death Points Beyond Materialism

The Axiom at the Heart of Human Existence

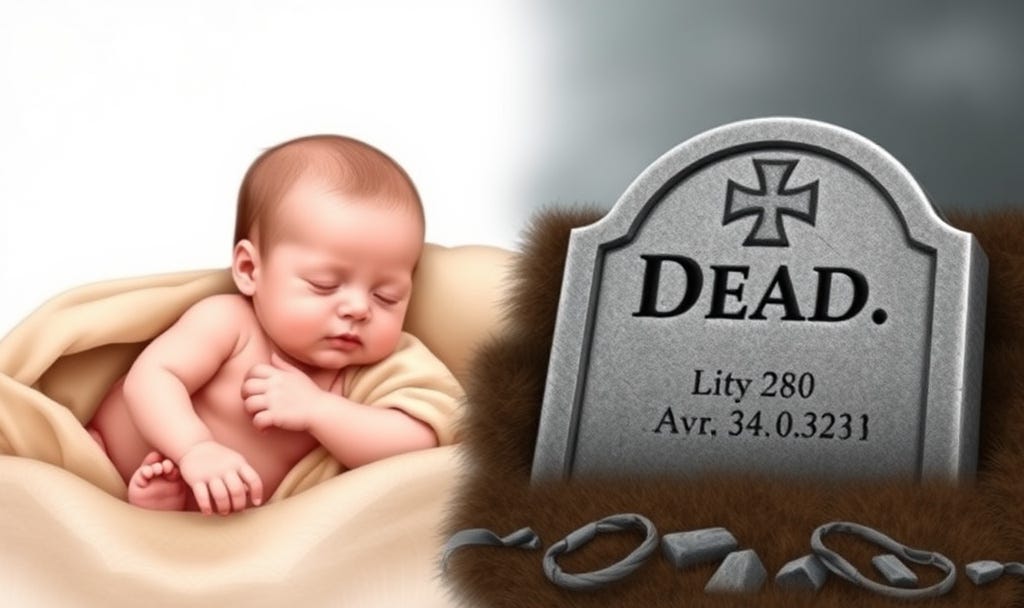

Every worldview must eventually face the question that none of us can avoid and all of us intuitively fear: What, exactly, is death? And more importantly, why is it permanent? That permanence, unwavering, universal, and unyielding, reveals something profound about the nature of life itself. If death were merely a mechanical failure, then like any machine, life ought to be mechanically restorable. But it isn’t. And that stubborn fact leads us to a reality larger than materialism is capable of explaining.

Here is the thesis plainly: The permanence of death exposes the insufficiency of strict materialism and points unmistakably to a non-material essence within every human being.

This is not mysticism. It is not escapism. It is the steady conclusion of reason, observation, and the unmistakable testimony of human experience.

The Fault Line Between Two Visions of Reality

Materialism claims that you and I are nothing more than remarkably complex arrangements of carbon, water, and electricity. Everything—from love to consciousness to hope—is reduced to neurons firing in predetermined patterns. In this view, your life is nothing more than chemistry running its course.

But standing opposite that worldview is the older, deeper, more human vision, one that says life is endowed, not assembled; that consciousness is breathed, not manufactured; that human identity transcends biology.

One of these views can explain why you replace a spark plug and your engine roars again. The other can explain why you cannot replace a heart and resurrect the person who once inhabited it. Which vision aligns with the world as it actually is?

The Machine Metaphor: A Dead End for Materialism

If humans were machines, death would be nothing more than a malfunction. Fix the broken part, restore the function. Replace the faulty circuit, revive the system. This is how engines behave, how computers behave, how mechanical systems behave. But human beings do not behave this way.

A heart can be surgically replaced. Lungs can be transplanted. Blood can be replenished. Tissue can be regenerated. Yet when life departs, no amount of intact physical structure can call it back. Something essential is gone, something not contained in the parts.

Materialism says life is the arrangement. But death shows us that life is not in the arrangement. Because once the life is gone, the arrangement can remain nearly perfect, and yet the human person does not return. This is the contradiction materialism cannot escape.

The Puzzle of the Self: Continuity Without Physical Continuity

Every atom in your body today is different from the atoms that made up your body ten years ago. Every cell has been replaced. Your physical composition is in constant flux.

Yet—you remain you.

Materialism cannot explain this. If identity were nothing more than matter, you should have become a different person a hundred times over. But you didn’t. The self remains. Identity persists. Consciousness endures through physical change.

How can something so constant arise from something so unstable?

The permanence of the self points to something beyond the physical substrate, a soul, an essence, a non-material continuity that anchors our existence. Without it, the very idea of “you” collapses.

Death as Irreversibility: A Philosophical Earthquake

At the microscopic level, physics is reversible. In theory, any arrangement of particles can be restored. Materialism depends on this assumption. If life is nothing but matter in motion, then theoretically, one could recreate it by restoring the matter to its previous state. But in practice and in principle, death is irreversible.

Once life departs, even momentarily, we cannot bring it back. Not with current tools. Not with imagined future tools. Not in principle.

Biology can describe the cascade of decay. But biology cannot explain why restoring the physical arrangement doesn’t restore the person. The parts can be present. The structure can be intact. And yet the life is gone. This is not a technical problem. It is an ontological one. Machines are revivable because their essence is material. Humans are not revivable because their essence is not material.

Steel-Manning the Secular Rebuttals

Intellectual honesty demands we consider the strongest materialist responses, generously and seriously.

Rebuttal 1: The biochemical environment collapses after death.

This simply means revival is biologically difficult, not metaphysically impossible. If consciousness were purely material, then future technology should in principle be able to reconstruct the “pattern.” But even in theory, this possibility rings hollow. Restoring the parts doesn’t restore the person.

Rebuttal 2: Identity is tied to neural states that degrade immediately after death.

This confuses memories with the self. Losing a memory does not erase the one who remembers. Death does not merely erase information. It erases the subject entirely.

Rebuttal 3: Life is too complex to restart once it collapses.

Complex machines are still machines. Complexity does not explain the metaphysical shift that occurs at death, the disappearance of the self. Materialism must explain why complexity produces consciousness and why consciousness ceases even when complexity remains. But it cannot.

Each rebuttal describes the biology of breakdown, but none explains the metaphysics of departure. They describe how the body declines, but not why the person is gone.